A thoughtful historical journey across time and space into the Bostonian imagination, as the city’s 400th birthday approaches, would begin for me with impressionistic visits to four places where architecture and landscape perfectly intersect: 17th century Boston Common fronting on Beacon Hill Downtown; 18th century Harvard Yard in Cambridge (the Old Yard around Massachusetts Hall, not the adjoining New Yard); the19th century Boston Public Garden in the Back Bay; and the 20th century Christian Science Plaza, also in the Back Bay.

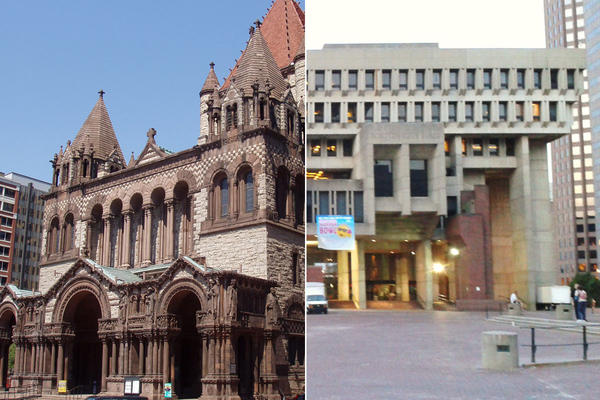

Add to these four a longer series of visits to landmarks ancient and modern, paired so as to show the continuities of area architecture through the centuries, and my judgment, after 45 years of studying architecture hereabouts — the first edition of my Built in Boston,City and Suburb was published by the University of Massachusetts Press in 1979 — is that Boston’s characteristic architecture and its chief architectural legacy is very different than many might imagine. In fact, as of now, the two pieces of architecture in Boston, historically, that stands out as most globally significant are Trinity Church and — gasp — the new Boston City Hall.

“Granite is peculiarly Boston’s stone,” the 19th century Bacon’s Handbook of Boston observed. Certainly the city’s first significant architecture, the venerable King’s Chapel of 1754, is of granite. And so is the great symbol of Boston’s emergence on the world stage, the magnificent obelisk, 221 feet high of sheer Quincy granite, 6700 tons of it, that rises so majestically over the Charlestown part of the Boston skyline: the Bunker Hill Monument.

Visitors over the years have noticed what a granite town Boston is. Walt Whitman, for instance, in the 1860s when he wrote startlingly of one example of the many ranges of stores and wharf buildings around Boston Harbor, then a teeming center of world-wide commerce, that it must surely be “one of the finest pieces of com[mercial] architecture in the world.” He described it only as of “rough granite,” and pronounced it “noble” in design.

Noble those harbor-front buildings seem to me too, not only in the way so many architectural authorities have called granite “the noblest of all building stones” — I am quoting Walter Kilham’s Boston After Bulfinch (1946) — but in the way the music of Beethoven struck 19th century Boston. To this day only that one composers name surmounts the stage of Boston’s Symphony Hall, emblematic of the fact that Beethoven’s work became in the 19th century the musical expression — da da da dum — of Boston Brahmin Unitarianism, which has been called the “Boston religion.” It was a favor the composer returned; for Beethoven was a follower of the leading Boston Unitarian divine of that era, William Ellery Channing. Look a Bulfinch’s magnificent Massachusetts General Hospital building of the 1820s — “Beethoven in Granite.”

“The Boston Granite Style, as it was called even in its own day,” historian James O’Gorman writes, spread down the Atlantic seaboard to New Orleans and up the Pacific seaboard to San Francisco, and according to another architectural historian, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, constituted “a highly original sort of basic classicism” more than worthy of comparison with the work of the leading European rationalist architects of the d19th century, Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Sir John Soane.”

The work of O’Gorman, the leading Richardson scholar, has also shown that the Granite Style was a key influence on the “massive”, “quiet” and “lithic” work of Henry Hobson Richardson, the Boston architect whose work was the first American architecture to achieve transatlantic stature. Echoes of Richardson’s Copley Square masterpieces may still be seen from the City Hall of India’s largest city to civic towers in The Netherlands and Finland, never mind also in the work in Chicago of the father of American modernism, Louis Sullivan, the only man Frank Lloyd Wright ever called master.

Almost a century later, in the 1960s, Modernist scholars and critics saw the 19th century Boston Granite Style again as pivotal to the formation of Boston’s iteration of the Heroic Concrete Style, as revealingly Bostonian in the 20th century as Richardson’s had been in the 19th century. A distinct effort by Boston architects to revisit and renew the characteristics they liked in the old granite work, New York Times critic Ada Louise Huxtable explained what they were so admiring of. The old work, she wrote, was “a unique type of stone-slab design in which the structural blocks were used with almost 20th century directness and unprecedented functional severity.” Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the mid 20th century dean of American architectural criticism, agreed. The waterfront ranges Whitman had spoken of, Hitchcock agreed, were “hardly equaled anywhere in the world.”

One scholar after another has judged well of the mid 20th century Bostonian effort. Critic Donald Lydon described Frederick Stahl’s splendid concrete office building at 70 Federal Street, for example, as “a Brahmin, a true descendant of the of the [19th century] granite slab skeletal buildings of the waterfront . . . .very lean and understated, polite, rational and charged with energy.” Even more pointedly, the distinguished architectural historian William J. R. Curtis, concluded: “if there is a ‘Boston School’ of architecture” it would be found, he thought, in “the plain geometrical forms”, “no-nonsense, no-frills” design and “bare concrete finishes” of the mid-20th century Concrete Style.

Boston’s achievement in this respect caught Curtis’s attention because he held the view that civic architecture in the modern period must strive for the same monumentality as in Classical times, without any implications of Fascist intimidation. Where better, he thought, to explore “how to handle public buildings with the appropriate degree of presence and accessibility, to establish the terms of a democratic monumentality . . . [for] the liberal-minded” than in the New England capital?” Adding, “monumentality is a quality in architecture which does not necessarily have to do with size, but with intensity of expression.”

Thus it is that a critical and scholarly consensus emerged that Boston’s second contribution to world architecture, after the 19th-century Richardsonian chapter, was the Bostonian iteration of mid 20th century Heroic Concrete architecture. It is a consensus that has been borne out by subsequent history.

This is why Trinity Church of 1877 and the New Boston City Hall of 1962 — together with the Boston Public Library in Copley Square (arguably the greatest American public building, rivaled only by the National Capitol in Washington, and only historically, not architecturally) may be said to be with the State House, Baker House and the Institute Chapel at MIT, Sever Hall at Harvard, and the Hancock Tower in the Back Bay — Boston’s architectural crown jewels.

The detractors of the newer style today problematically label it “Brutalist”; its contemporary admirers call it “Heroic Expressionism”, or just “Heroic.” No more than the original Boston Granite Style was the Heroic Concrete Style ever a popular taste — of the sort the Colonial Revival is, for instance. And it was not until the mayor of Boston’s core city, Thomas M. Menino, urged the tearing down Boston City Hall, and others felt even the magnificent Christian Science Plaza in the Back Bay was

threatened, that defenders emerged to remind that some of Richardson’s best work had, in fact, been destroyed in the 1930s, and to counsel caution, lest popular culture — with its love of red brick and picturesque effect — waylay us into forgetting the admonition of economist John Kenneth Galbraith in his keynote address to a Harvard Design Conference: “beauty no more than measles or syphilis is to be entrusted to the uninstructed intellect.”

None have proved more dedicated in this effort than the partners of the Boston architectural firm of over,under, who mounted in 2009 a magnificent exhibition on the Heroic Concrete Style as developed in Boston at their pinkcomma gallery in the South End. And Mark Pasnik, Chris, and Michael Kubo have now followed up with the first book length study of Modernist architecture in Boston in twenty five years: Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston. They place the Boston work in the context of the world-wide movement of building in concrete after World War II, of course, but point out that “in Boston it was deployed in more numerous and diverse civic, cultural and academic projects than in any other major U.S. city.” Essays by four historians — Joan Ockman, Lizabeth Cohen, Keith M. Morgan and myself — complete the work, and it is in my essay that I explore the issues raised here and suggest that Boston’s most revealing architecture, historically, and its greatest contribution to world architecture, are the two chief progeny of the 19th century Boston Granite Style, the 19th century achievement of Henry Hobson Richardson and Boston’s iteration of 20th century Heroic Concrete Style.

Nary a red brick in sight.